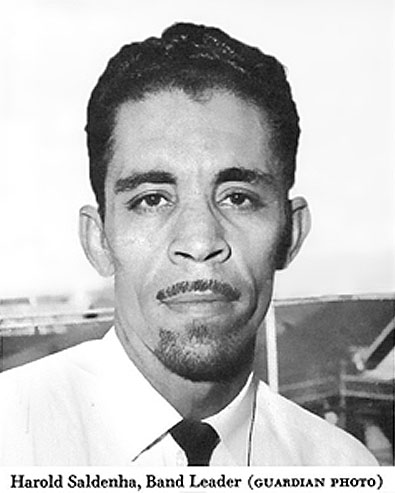

Harold "Sally" Saldenah

The Historian

by Dylan Kerrigan & Nicholas Laughlin

from the March/April 2005 Issue (No. 65) of Caribbean Beat

In all art-forms, creativity balances tradition – the lessons of the achievements of the past – against originality. Complete breaks with what has gone before are rare. Most Carnival designers begin their careers as apprentices to older masters, absorbing the skills and knowledge they need before they can make their own unique contributions to the ongoing tradition.

Born in the east Port of Spain district of Belmont in 1925, Harold Saldenah – universally known as “Sally” – began his Carnival career in the years immediately after the Second World War, as an assistant to now almost forgotten bandleaders like Harry Basilon and Harold Tang Yuk, and, most importantly, Mansie Lai. (In turn, among Saldenah’s early masqueraders were future bandleaders Stephen Lee Heung, Bobby Ammon, and Edmond Hart.)

These were the days when Trinidad’s different social groups still had separate Carnival experiences – the “white” bands drove through Port of Spain in their elevated lorries, while “parading the streets on foot in costume…was perceived as a ‘black’ thing”, as one historian has put it.

But in the early 50s change accelerated. Lighter-skinned masqueraders, drawn by the increasingly attractive costumes of bandleaders like Saldenah and his contemporaries, came down from their lorries, reconnecting their mas with the streets.

Sally’s historical presentations, intensely researched and scrupulously fabricated, worked as a catalyst for this change. As designers looked beyond traditional characters and biblical stories for their subject matter, new masqueraders from across the social spectrum swelled the sizes of the leading bands from the dozens to the hundreds.

Mansie Lai, Saldenah’s early mentor, had been greatly influenced in his themes by the Hollywood films that were so popular in Trinidad’s cinemas in the 1930s and 40s. In 1952, when Saldenah designed his own first band, he took inspiration from the 1951 film extravaganza Quo Vadis, set in New Testament times. Saldenah used still pictures distributed by the movie studios to guide his costume designs; he even wrote to Hollywood for more photos. Unable to afford metal, and with plastic not yet in common use, he made his first legionnaires’ helmets from papier mâché over clay moulds.

Harold Saldenah: Band of the Year Titles

1955 Imperial Rome 44 BC to 96 AD

1956 Norse Gods and Vikings

1958 Lost City of Atlantis

1959 Crees of Canada

1964 Mexico 1519 to 1521

1968 El Dorado, City of Gold

Over the next decade Saldenah produced a series of historical epics, remarkable for the magnificence and splendour of their costumes. Most celebrated of all, his 1955 presentation Imperial Rome 44 BC to 96 AD astounded masqueraders and spectators with its elaborate cast of characters – centurions, gladiators, vestal virgins, and the 12 Caesars, including Nero in a 20-yard cape of purple velvet. Saldenah’s insistence on accuracy forced his Roman soldiers into short skirts.

Previously, bare flesh had been considered inappropriate. But Sally dispensed with tights and political correctness. His legionnaires learned to reflect the realism of the era they portrayed. He used tooled leather and real copper breastplates created by Ken Morris, contributing to a new tradition of metalwork in Carnival design. No one was surprised when Imperial Rome won Saldenah the first of his six band of the year titles.

During the 60s, as more women joined the masquerade and bands grew even larger (his Mexico 1519 to 1521 crossed a thousand in 1964), Saldenah split up the mass of costumed revellers into different sections, each depicting one aspect of the overall portrayal. He was thus a pioneer of “section mas”, which soon became the convention. With their different colours and themes, each complete with flag bearer and title, the sections came together in rapid succession to tell a larger story.

In the mid-60s, “fantasy” portrayals began a trend away from authentic historical themes, bringing new possibilities to designers and bandleaders. Saldenah’s imagination rose to the challenge, and with his 1968 presentation, El Dorado, City of Gold, he combined history and fantasy brilliantly. The shiny foil he used on the costumes created a glistening spectacle in the setting sun. Other bandleaders quickly followed his lead.

In 1976, to celebrate his 25th year as a bandleader, Saldenah presented a personal retrospective called A Sailor Is a Sailor, recreating each of his previous bands in the form of a traditional fancy sailor. The following year he moved to Canada, where he brought his expertise to the Trinidad-style Caribana Carnival. But in 1983, for the 200th anniversary of Trinidad Carnival (the first French settlers had arrived in 1783), he came back home to present Masquerade to Carnival, a 40-section tribute to the history of the festival, with costumes celebrating dozens of traditional characters. The historian of ancient civilisations had become the historian of his own art-form.

Sally died from cancer in June 1985. He said he never felt afflicted by the disease, preferring fresh coconut water from Savannah vendors to the drugs recommended by his doctors. Two days before his death, as he was carried on a stretcher from his home to the hospital, he turned to those around him and said, with a masquerader’s smile, “Look how I’m going out as an African king!”